One of the most important milestones in computing was figuring out how to keep data alive after a program stops. In the beginning, both the code and the data lived in memory. If the program crashed, the data disappeared too. That’s why engineers created file systems, so data could be saved on disk and loaded again later.

For small programs, this worked fine. But as systems grew, people needed better ways to store and manage data. That’s when SQL came in.

SQL is still everywhere today. It powers databases like Postgres and MySQL.

Common Criticisms of SQL

SQL is dying

SQL remains a backbone of data persistence in most industries.

SQL doesn’t work well with Python’s AsyncIO

Python’s asyncio is asynchronous by nature, while many older SQL libraries are synchronous. This can create friction, but modern tools like SQLAlchemy 2.0 and asyncpg address this perfectly, allowing fully asynchronous database interactions.

SQL is slow

Poorly written queries can be slow but that’s not SQL’s fault. With proper indexing, caching, and query design, SQL can be incredibly fast.

Should you use an ORM?

First, what’s an ORM?

ORM (Object-relational mapping) lets you work with the database using code instead of writing SQL directly. It’s helpful when you want to avoid thinking about SQL or when your data model is simple.

But ORMs aren’t perfect. For complex queries or performance-heavy parts of your app, they can get in the way.

In Python, SQLAlchemy is the de-facto standard. It offers both an ORM and a “Core” layer that allows for raw SQL construction. In this series, we will use a hybrid approach: using SQLAlchemy for connection management and basic mapping, but keeping our architecture flexible enough to write raw SQL if needed.

Installing PostgresSQL using Docker compose

Docker is an excellent tool to avoid bringing garbage to our computers. We will use it to run PostgreSQL.

services: postgres: image: postgres:17-alpine environment: POSTGRES_PASSWORD: postgres POSTGRES_USER: postgres TZ: America/Bogota PGTZ: America/Bogota networks: - adaptable_backend_python volumes: - postgres_data:/var/lib/postgresql/data ports: - 5432:5432 healthcheck: test: ["CMD-SHELL", "pg_isready"]

networks: adaptable_backend_python:

volumes: postgres_data:Running the postgres service

To check if the service is working, let’s add a new command to our Makefile or just run it directly:

docker compose up -d --waitIntegrate PostgreSQL to our Python project

Following the guidelines of the project, the database stuff will reside inside src/core/database folder.

To begin, install the connector libraries. We will use SQLAlchemy (for abstraction) and asyncpg (for high-performance async connection).

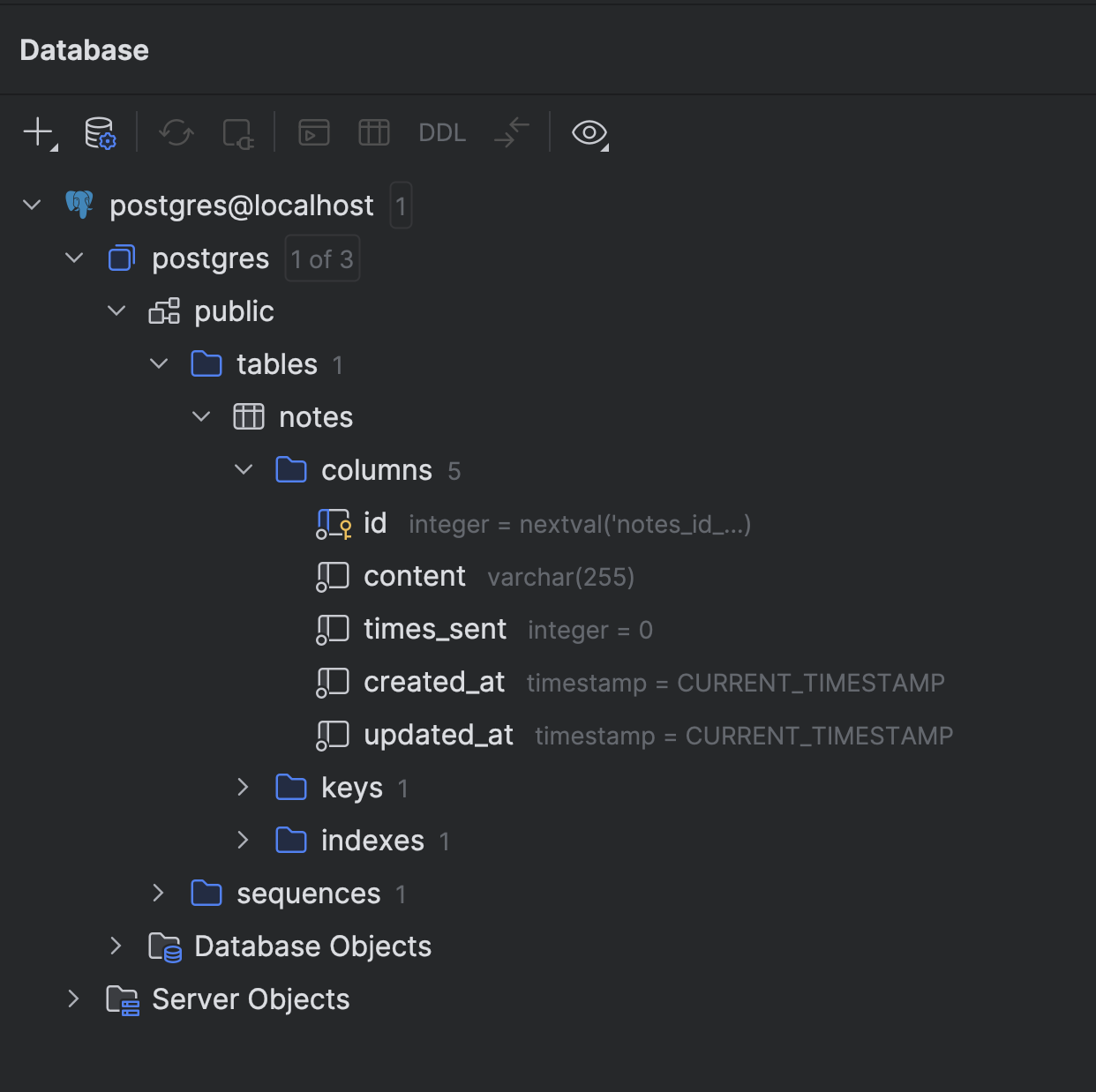

uv add sqlalchemy asyncpgIn the ER-diagram all entities have in common 3 attributes, id, created_at, and updated_at. Let’s create src/core/database/base_entity.py.

from datetime import datetimefrom typing import Optionalfrom pydantic import BaseModel, Field

class BaseEntity(BaseModel): id: Optional[int] = None created_at: Optional[datetime] = None updated_at: Optional[datetime] = NoneRepository pattern

For many years I’ve seen numerous debates about ORM, DAO and other persistence patterns. One of the most adaptable is the Repository Pattern, which basically tells the application’s controllers, “I will take care of persistence”.

Creating the interface i_repository.py using Python’s Protocol for structural typing.

from typing import Protocol, TypeVar, Optional, List, Any

T = TypeVar("T")

class IRepository(Protocol[T]): async def find_by_id(self, id: int) -> Optional[T]: ... async def find_all(self) -> List[T]: ... async def create(self, data: Any) -> T: ... async def update(self, id: int, data: Any) -> Optional[T]: ... async def delete(self, id: int) -> bool: ...To avoid hardcoding things let’s create database_engine.py:

from enum import Enum

class DatabaseEngine(str, Enum): NOSQL = "mongodb" SQL = "postgres"Adding the database environment variables

Update .env:

TZ=America/Bogota

# Database SQLDATABASE_URL=postgresql+asyncpg://postgres:postgres@localhost:5432/postgresDATABASE_ENGINE=postgresNote the postgresql+asyncpg scheme, which tells SQLAlchemy to use the asyncpg driver.

Create the SQL setup

We will create a raw SQL migration to set up our table.

BEGIN;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS notes ( id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY NOT NULL, content VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL, times_sent INT NOT NULL DEFAULT 0, created_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP, updated_at TIMESTAMPTZ NOT NULL DEFAULT CURRENT_TIMESTAMP);

COMMIT;Running migrations

We’ll create a simple Python script to run these migrations using asyncpg directly.

import asynciofrom pathlib import Pathimport asyncpgfrom src.core.configuration import config

class SQLMigrate: def __init__(self): self.migrations_dir = Path("src/core/database/sql/migrations") self.database_url = config.get("DATABASE_URL").replace("+asyncpg", "")

async def run(self) -> None: print("Running migrations...")

if not self.migrations_dir.exists(): print(f"Migrations directory not found: {self.migrations_dir}") return

conn = await asyncpg.connect(self.database_url) try: for file in sorted(self.migrations_dir.glob("*.sql")): print(f"Running migration: {file.name}") sql = file.read_text() await conn.execute(sql) print("✓ Migrations completed successfully") except Exception as e: print(f"✗ Migration failed: {e}") raise finally: await conn.close()

if __name__ == "__main__": migrate = SQLMigrate() asyncio.run(migrate.run())Run it with:

uv run python src/core/database/sql/migrate.py

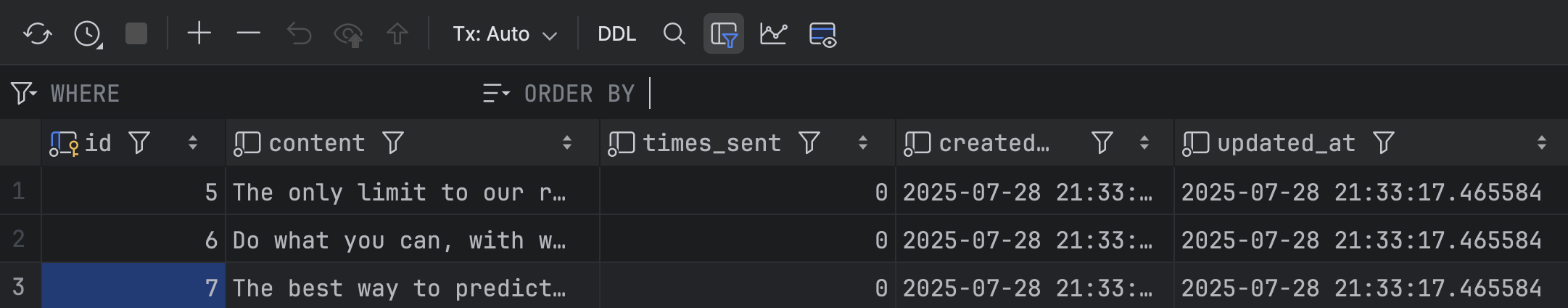

Creating the seeders

Similar to migrations, we can create a seeder script.

INSERT INTO notes (content)VALUES ('The only limit to our realization of tomorrow is our doubts of today.'), ('Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.');And a seeder.py script (similar to migrate.py) to execute it.

Implementing the SQLRepository

Now we implement the repository using SQLAlchemy.

from typing import Type, TypeVar, List, Optional, Anyfrom sqlalchemy.ext.asyncio import create_async_engine, AsyncSessionfrom sqlalchemy import textfrom src.core.configuration import configfrom src.core.database.i_repository import IRepository

T = TypeVar("T")

class SQLRepository(IRepository[T]): def __init__(self, table_name: str): self.table_name = table_name self.engine = create_async_engine(config.get("DATABASE_URL"))

async def find_all(self) -> List[T]: async with AsyncSession(self.engine) as session: result = await session.execute(text(f"SELECT * FROM {self.table_name}")) return result.mappings().all()

async def create(self, data: dict) -> T: columns = ", ".join(data.keys()) values = ", ".join([f":{k}" for k in data.keys()]) sql = text(f"INSERT INTO {self.table_name} ({columns}) VALUES ({values}) RETURNING *")

async with AsyncSession(self.engine) as session: result = await session.execute(sql, data) await session.commit() return result.mappings().first()

# ... implement other methods similarly[!NOTE] SQL Injection Prevention: We use named parameters (e.g.,

:id,:contentin values variable) in ourtext()queries. SQLAlchemy binds these safely using the underlying driver (asyncpg), protecting against SQL injection attacks. We avoid manual string concatenation for values.

Creating the NoteRepository

Now we create the NoteRepository that chooses the engine.

from src.core.database.i_repository import IRepositoryfrom src.core.database.database_engine import DatabaseEnginefrom src.core.configuration import configfrom src.core.database.sql.sql_repository import SQLRepository

class NoteRepository: def __init__(self): db_engine = config.get("DATABASE_ENGINE") self.repository: IRepository

if db_engine == DatabaseEngine.SQL: self.repository = SQLRepository("notes") elif db_engine == DatabaseEngine.NOSQL: # To be implemented pass

async def find_all(self): return await self.repository.find_all()

async def create(self, data): return await self.repository.create(data)Registering the NoteRepository

Update the DI container:

# ...from src.core.features.note.note_repository import NoteRepository

class Container(containers.DeclarativeContainer): # ... note_repository = providers.Singleton(NoteRepository)

note_controller = providers.Singleton( note_controller = providers.Factory( NoteController, note_repository=note_repository )Updating the NoteController

Inject the repository into the controller:

class NoteController: def __init__(self, note_repository): self.note_repository = note_repository

async def get_notes(self): return await self.note_repository.find_all()Complete the NoteRestController CRUD

Before completing the CRUD, let’s add a common response format that our REST API will use as a contract to standardize responses.

from typing import Generic, TypeVarfrom pydantic import BaseModel

T = TypeVar("T")

class SuccessResponse(BaseModel, Generic[T]): data: TA SuccessResponse class that receives a generic T to tell clients the response was successful (along with HTTP status 2xx). Now, let’s implement the rest of the methods.

from fastapi import APIRouterfrom fastapi import Path as PathParam, Bodyfrom src.core.features.note.note_dto import NoteDtofrom src.core.features.note.note import Notefrom src.core.features.note.note_controller import NoteControllerfrom src.core.container.container import containerfrom ..response_types import SuccessResponse

class NoteRestController: def __init__(self) -> None: self.note_controller: NoteController = container.note_controller()

self.router = APIRouter(prefix="/notes", tags=["notes"]) self._setup_routes()

def _setup_routes(self) -> None: self.router.add_api_route( "/", self.get_notes, methods=["GET"], response_model=list[NoteDto], response_model=SuccessResponse[list[Note]], summary="Get all notes", ) self.router.add_api_route( "/", self.create_note, methods=["POST"], status_code=201, summary="Create a new note", ) self.router.add_api_route( "/{id}", self.update_note, methods=["PUT"], summary="Update a note", ) self.router.add_api_route( "/{id}", self.delete_note, methods=["DELETE"], status_code=204, summary="Delete a note", )

async def get_notes(self) -> list[NoteDto]: return self.note_controller.get_notes() async def get_notes(self) -> SuccessResponse[list[Note]]: results = await self.note_controller.get_notes() return SuccessResponse(data=results)

async def create_note(self, payload: dict = Body(...)) -> None: await self.note_controller.create_note(payload)

async def update_note( self, id: int = PathParam(..., description="Unique identifier of note"), payload: dict = Body(...) ) -> None: await self.note_controller.update_note(id, payload)

async def delete_note( self, id: int = PathParam(..., description="Unique identifier of note") ) -> None: await self.note_controller.delete_note(id)

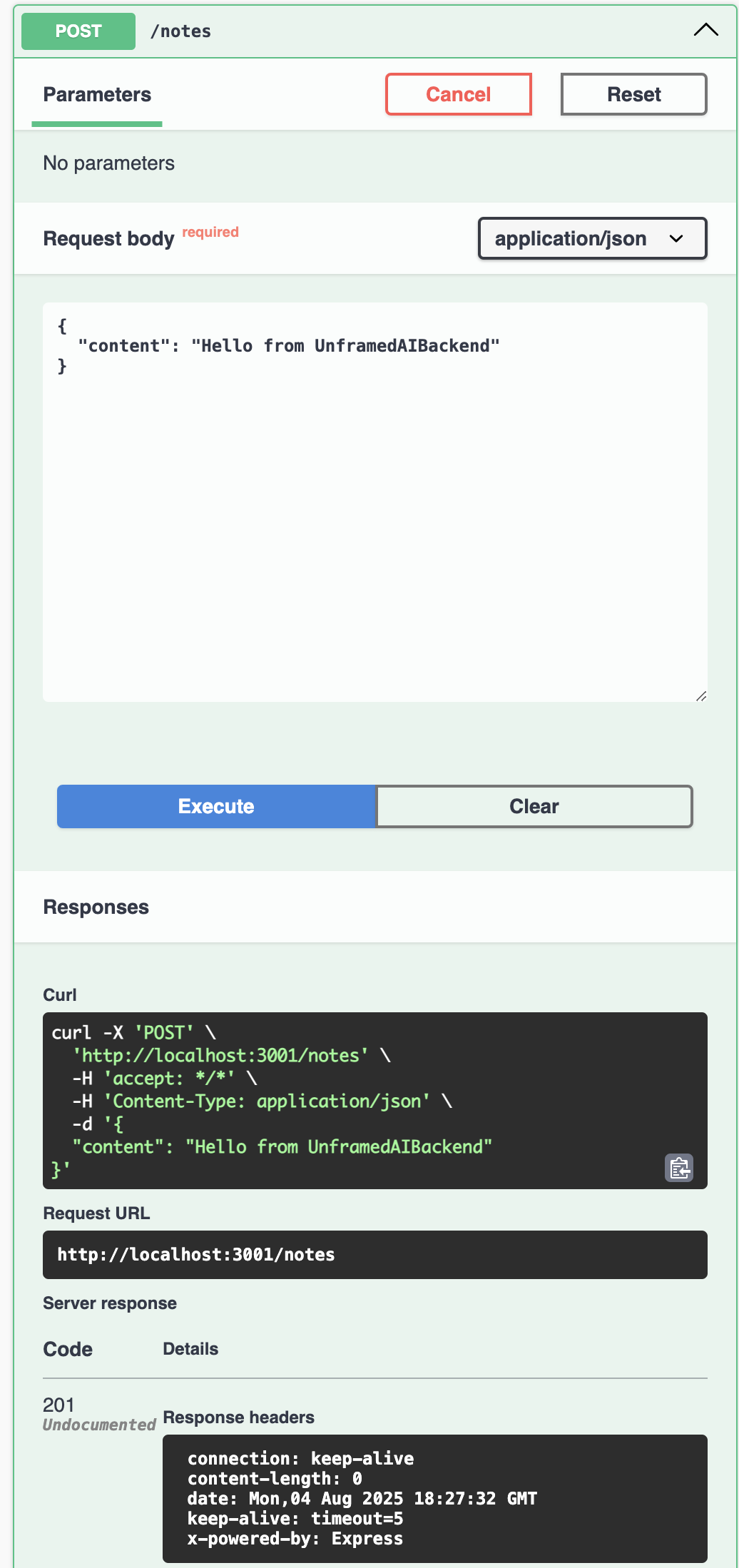

note_controller = NoteRestController()router = note_controller.routerWith FastAPI’s automatic OpenAPI generation, visiting /docs will show all endpoints with proper documentation.

Testing CRUD

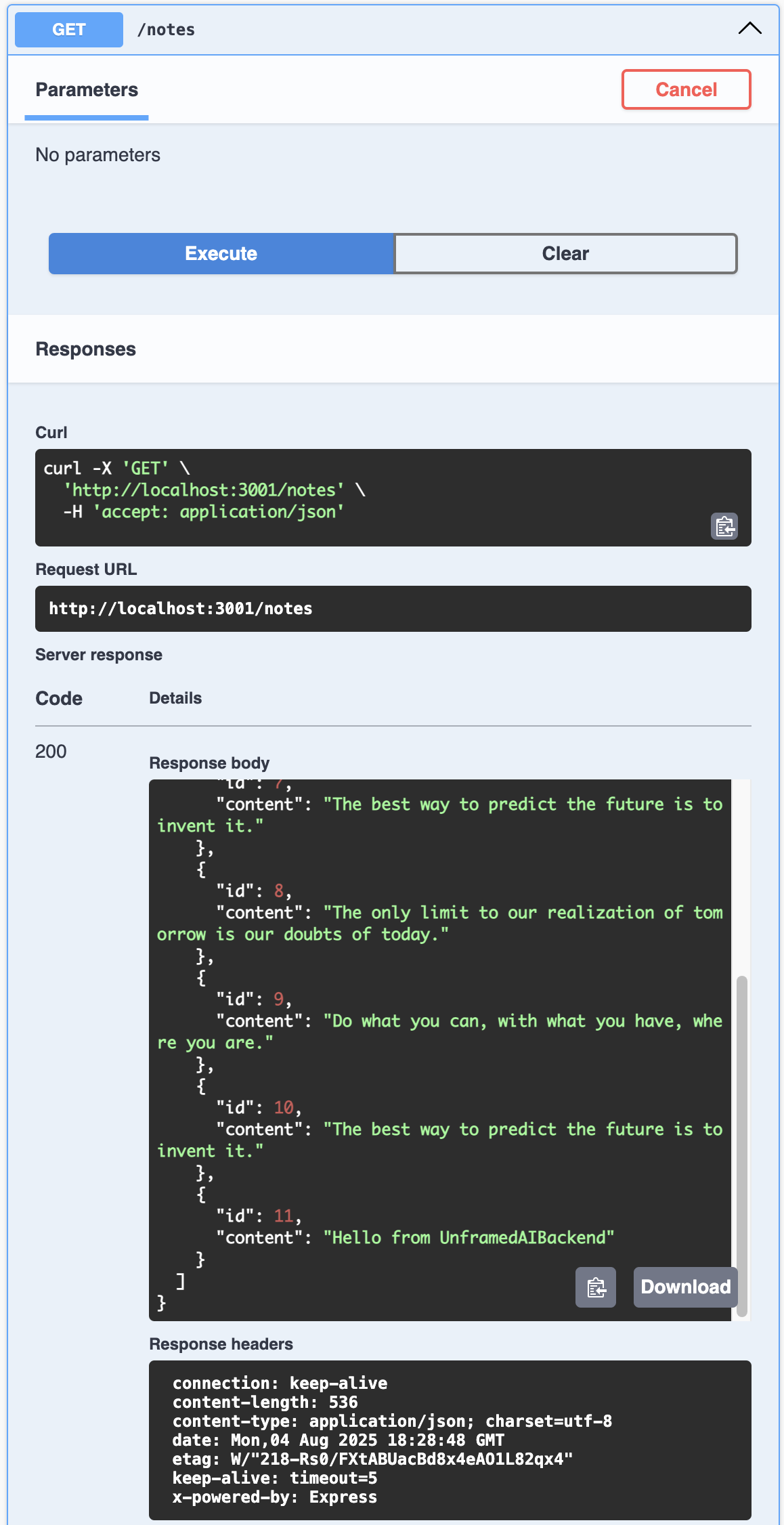

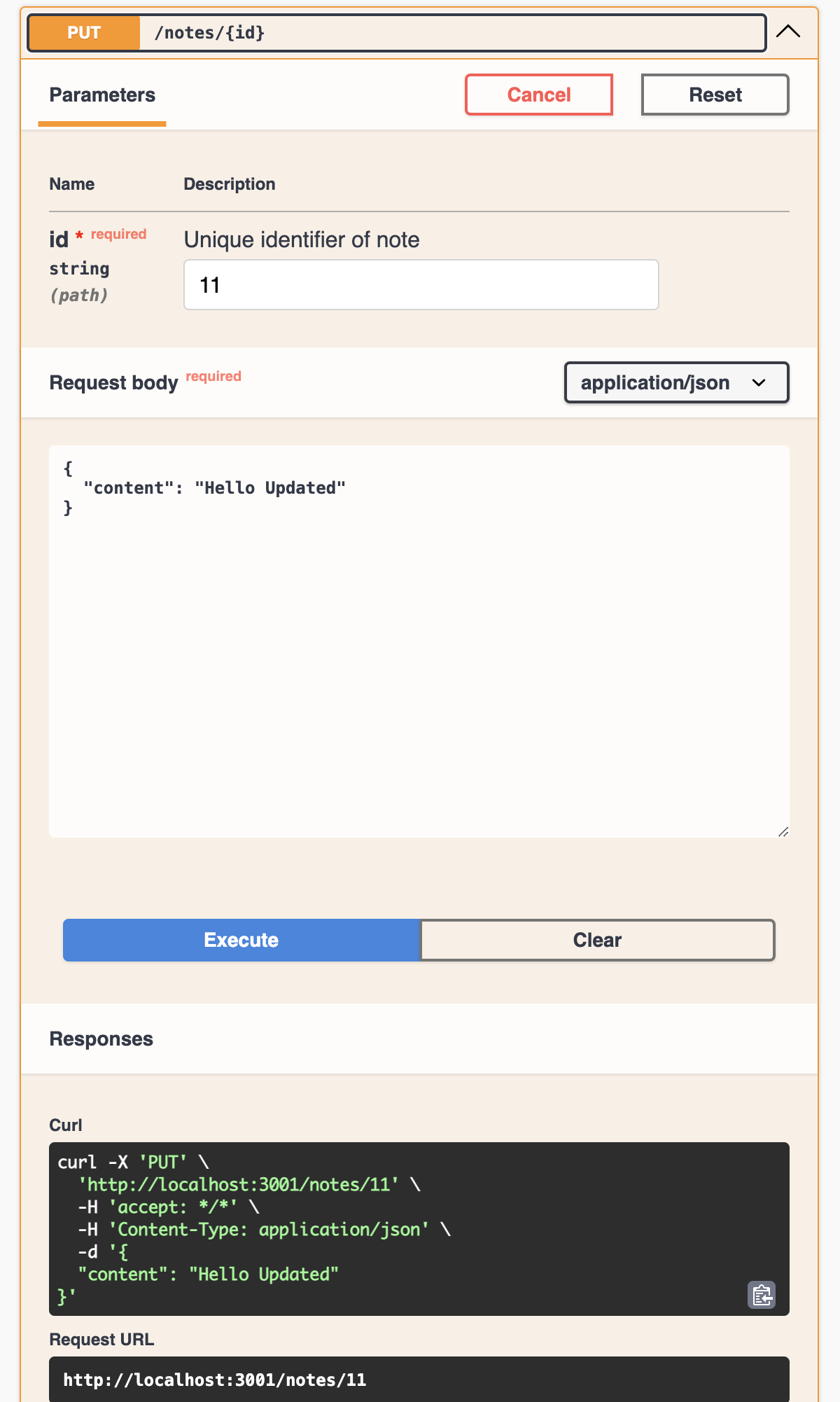

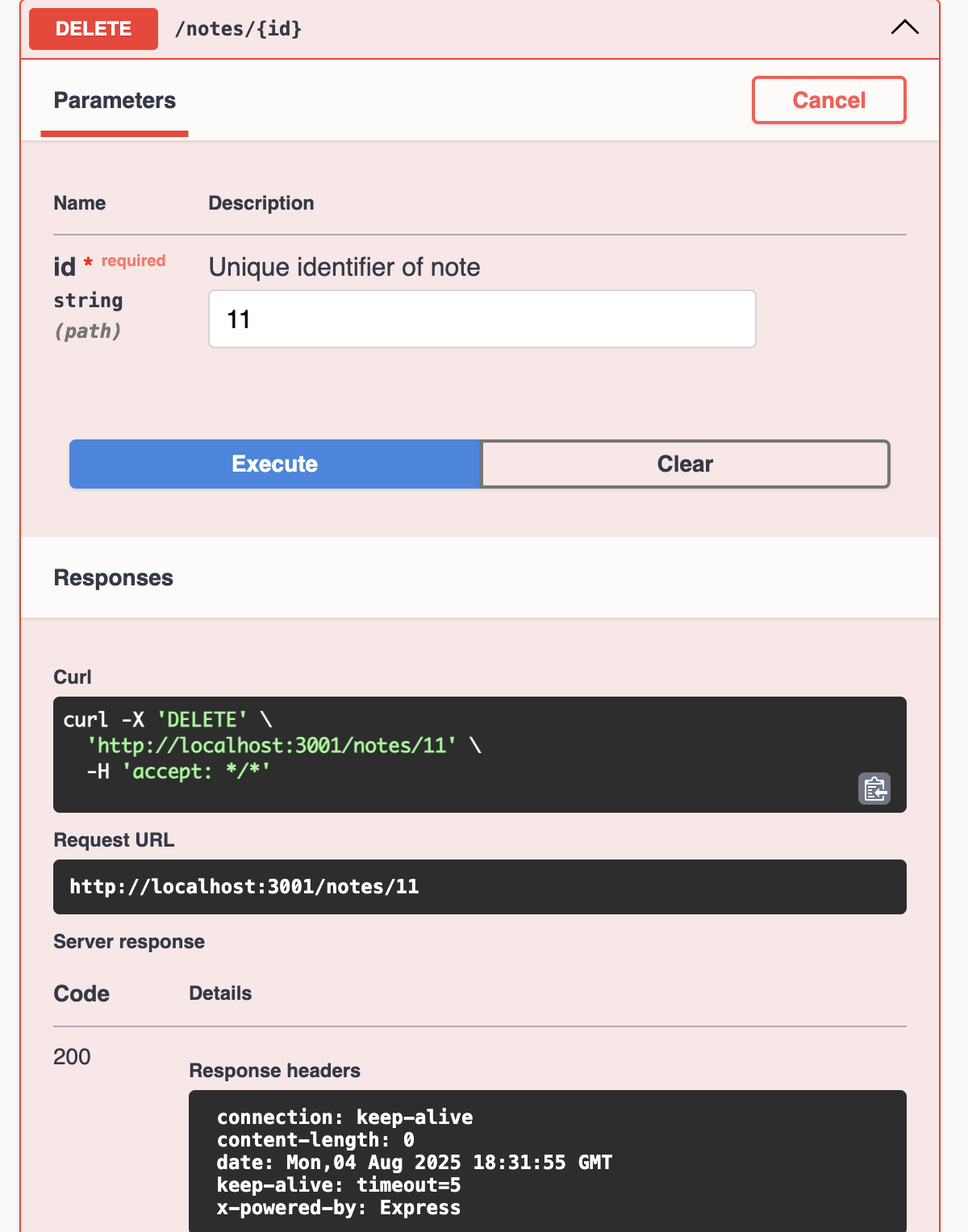

After adding all required steps, you can run the application to verify all methods work. Access /docs to test each endpoint interactively using FastAPI’s built-in Swagger UI.

make devVisit http://localhost:3000/docs and test each endpoint.

Create Note

Read Notes

Update Note

Delete Note

Conclusion

We have successfully integrated PostgreSQL persistence using a decoupled Repository pattern in Python. By using SQLAlchemy and asyncpg, we ensure high performance and async compatibility.

In the next article, we will switch to a NoSQL database without changing our business logic!